Memorandum to the Young Homosexual

I’ve seen you looking, boy.

No, of course not at an old queen like me, my southerly titties

sheathed in silk and sequins and Turkish cigarette smoke.

Still, I do have my admirers, even if you won’t find them

in the bars or the bathhouses or the brambles. We gather in my apartment

well east of Tompkins Square Park. Jimmy, Stephen, Reginald always

come. Henry and Lars, too. Good men all, though not without their

foibles. Stephen, for example, has always been paranoid. Still

fearful of arrest. Yes, even in my apartment. Even to this day. I know

it’s a bit out of the way, but the invitation is always open. Although the

refreshment is light—wine, cheese, crackers— and the attire is casual, it is

still a royal court of sorts. All right, a salon then, if you insist.

Or perhaps an oral history archive or a museum of relics?

I’ve seen you looking, boy.

It takes one to know one, and I know that of which I speak.

In my day, you see, interfacing wasn’t virtual.

Encounter required touch. And to make that happen, the body and its

language had to be read, a literacy which required years for mastery.

There was nothing instinctive or “gut” about it.

The stakes were high, mind you. You could end up in handcuffs—

and I don’t mean the velvet ones—in a cell with pimps and killers

and with your name on a list in the papers and out of a job.

You could end up pummeled or slashed or slain and dumped

into the river or beneath an overpass, the traffic whirring overhead—

the stuff of pulp novels minus the campy covers or noir

without the hard-nosed dick to rescue you. Of course, you still could.

I’ve seen you looking, boy.

I know of the gaze drawn to strapping workmen.

Sometimes I saw them on the way to my office job,

shirtless at a building site, whistling at women going by,

eating a sandwich in wax paper and swilling I-never-knew-what

from a blue metal thermos. I still recall that shade of blue.

Sometimes in the diner Helena, my girlfriend from the office,

and I favored for lunch. Their pastrami sandwiches were legendary.

No, Helena was not my beard. She was a friend, a worksite-specific one,

to be sure. Sometimes I would see men by the piers at night or early

morning, when the ache got the better of me and repartee and bourbon

were no longer enough. My reading skills were most essential

in the darkest dark, without aid of moon or flash- or streetlight.

I’ve seen you looking, boy.

And I am not impressed; you have much to learn.

You need to master the art of the surreptitious glance.

The eye should lightly graze; avoid the full-fronted stare,

but don’t assume a position of coyness, either.

You aren’t a demure maiden or a geisha.

Don’t conceal your smile by your hand or shadow.

Your shoulders should not slouch,

but they needn’t be militarily set back, either.

You will have to do all this in a matter of seconds. Little thing like you,

your life may depend on it. And no, that’s not hyperbole.

Is there a Helena in your life? Come to our next gathering, sweet pea.

I’m sure Lars can rustle up just the right young lady for you.

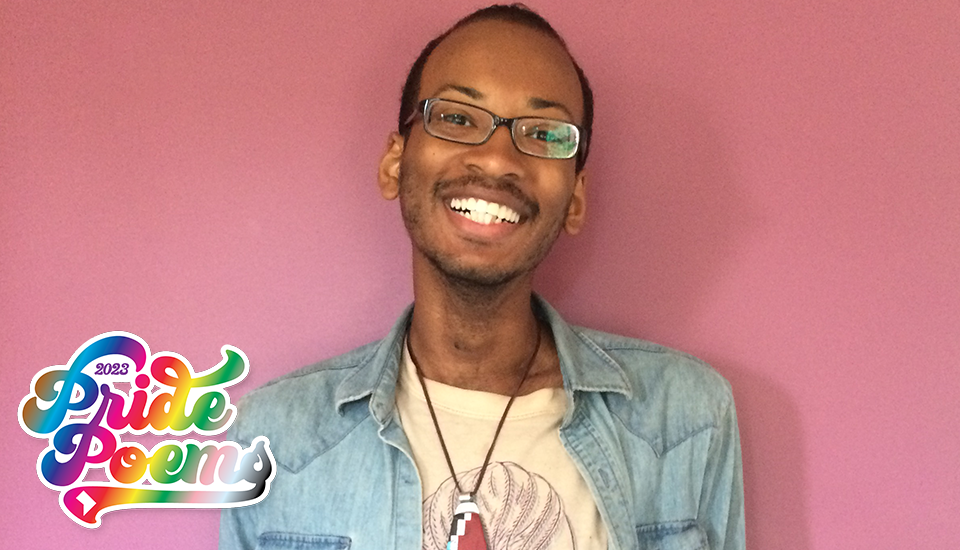

Yermiyahu Ahron Taub is a poet, writer, and Yiddish literary translator. He is the author of two books of fiction, Beloved Comrades: a Novel in Stories (2020) and Prodigal Children in the House of G-d: Stories (2018), and six volumes of poetry, including A Mouse Among Tottering Skyscrapers: Selected Yiddish Poems (2017). Taub’s most recent translation from the Yiddish is Dineh: an Autobiographical Novel by Ida Maze (2022).

Yermiyahu Ahron Taub is a resident of Brookland.